Background Knowledge:

All connected devices require a communication protocol of one kind or another in order to inform the other device of what task it should perform next. Or as to the result of the task the device has performed. Now there are plenty of hardware based approaches I have worked on, and several more software based ones. Due to the vast magnitude I will just briefly touch upon some of them, feel free to contact me if you want a more indepth explanation of how the different protocols work.

Quick Run:

To simplify your research I have seperated the communication protocols that I worked with based on the underlying hardware.

Analog Wires:

This field encompasses all the analog wire protocols.

SENT Protocol:

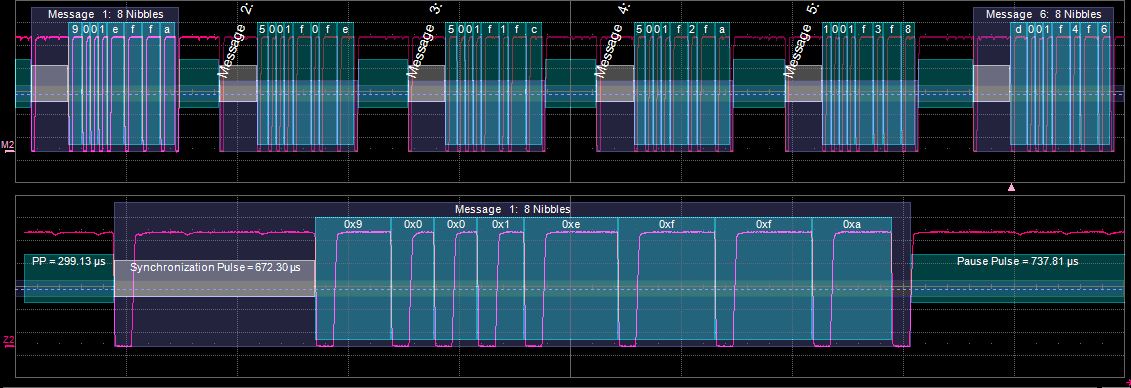

The SENT protocol is the simplest protocol that I know off which uses analog wires, with a digital output. Below is a sample of some of the SENT output.

This is a protocol commonly used in high resolution sensors, for the simplicity in implementation. This uses 3 wires for communication, a power, ground, and signal wire. The signal alternates between high and low, and all transmissions are broken into nibbles (4 bits). There are 8 nibbles in 1 SENT message. This is a one way asynchronous communication protocol.

UART Protocol:

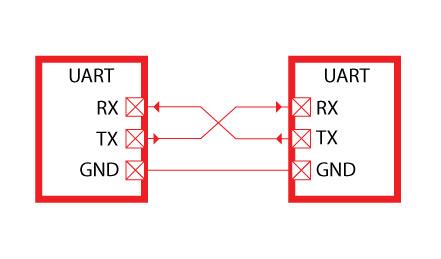

This is another protocol that gives a digital output. Unfortunately UART is very large with quite a few different modes. This is the most commonly used protocol, to the point I will only briefly touch on how it works. Below is the wiring diagram.

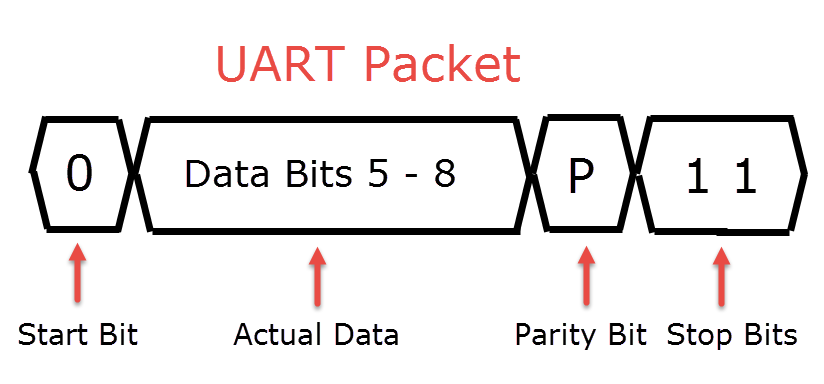

Unfortunately they miss the power line connection, not necessary however I found it helps with debugging certain cases. Both devices can transmit and receive at the same time, as most devices have seperate UART buffers in hardware for sending and recieving. Packet structure for UART is as follows:

There are also technically request to send, and clear to send lines, but these are rarely used for most applications.

It is common to use interrupts for UART, I talk more about interrupts and when to and when not to use them here.

USART Protocol:

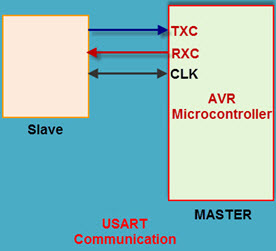

While UART works for a lot of basic applications, the issue stands when the 2 devices have differing clocks. One way of fixing this is using a synchronization clock, USART handles this by having the transmitting device set the clock speed for the recieving. Making it receive on each rising edge.

Now you can run USART without the synchronization clock, making it UART.

I2C Protocol:

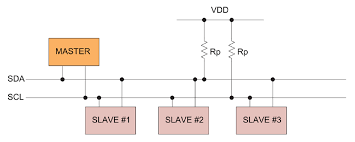

This is another master-slave protocol, main annoyance with this one is getting data from the slave. Below is an example of the wiring:

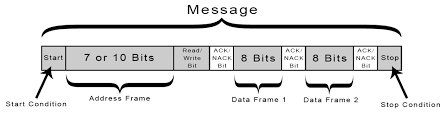

Now to make sense of this we should also look at an example packet sent:

Now the basis of how I2C works is, there is a clock which is turned on when you attempt to write/read from an address. You start by sending the address as well as the command and reading from it. With PIC MCUs there were issues reading from I2C, so the solution was to keep transmitting 0 values while the slave was trying to communicate back. In most cases however I2C is a protocol that is incredibly annoying to work with and you end up having to create a form of SPI protocol in order to properly select the slaves you want.

SPI Protocol:

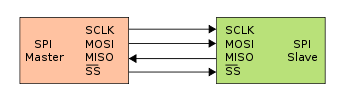

This is another master-slave protocol, and from my experience is a better fit than I2C for most applications, even though it requires more wires. SPI requires only 4 wires, a wiring diagram is shown below:

Since the packet structure is open to interpretation on SPI, I will instead provide some code for transmitting and receiving a byte on SPI.

/*

* Simultaneously transmit and receive a byte on the SPI.

*

* Polarity and phase are assumed to be both 0, i.e.:

* - input data is captured on rising edge of SCLK.

* - output data is propagated on falling edge of SCLK.

*

* Returns the received byte.

*/

uint8_t SPI_transfer_byte(uint8_t byte_out)

{

uint8_t byte_in = 0;

uint8_t bit;

for (bit = 0x80; bit; bit >>= 1) {

/* Shift-out a bit to the MOSI line */

write_MOSI((byte_out & bit) ? HIGH : LOW);

/* Delay for at least the peer's setup time */

delay(SPI_SCLK_LOW_TIME);

/* Pull the clock line high */

write_SCLK(HIGH);

/* Shift-in a bit from the MISO line */

if (read_MISO() == HIGH)

byte_in |= bit;

/* Delay for at least the peer's hold time */

delay(SPI_SCLK_HIGH_TIME);

/* Pull the clock line low */

write_SCLK(LOW);

}

return byte_in;

}This is transmission using bit-banging instead of dedicated hardware for the transmission.

RS Family Protocol:

There are 3 main protocols in this family namely RS232, RS422, and RS485.

These are all found on old computers as serial ports, they are currently being replaced by USB and other protocols, in the meantime howevere there are still quite a lot of old electronics that still use these ports. The protocols themselves are fairly self explanatory. So here are wiring diagrams for the protocols. The order is RS232, RS422, RS485:

CAN Protocol:

CAN is the king of automotive communications, most automotive companies use CAN. The reason for this is primarily due to the fact that there are very nice debugging tools for the CAN protocol, and it allows for error checking built in. This is a differencial line protocol, which means there is no ground/voltage but rather the difference between 2 voltages is measured.

Below is a sample CAN Packet:

Now below is some code from one of the projects I worked on, this is for accessing the CAN bus on Linux (Jetson TX2).

/*

* Author: Michael Buchel

*/

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <errno.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <net/if.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <sys/ioctl.h>

#include <linux/can.h>

#include <linux/can/raw.h>

#include <logging.h>

#include <can.h>

/*

* start - starts a can device using the device name

* @str - name of the device

*/

void CAN::start(const char *str)

{

struct sockaddr_can addr;

struct ifreq ifr;

fd = socket(PF_CAN, SOCK_RAW, CAN_RAW);

if (fd < 0) {

LOG_ERROR("Could not open socket, error: %s", strerror(errno));

exit(1);

}

strcpy(ifr.ifr_name, str);

ioctl(fd, SIOCGIFINDEX, &ifr);

addr.can_family = AF_CAN;

addr.can_ifindex = ifr.ifr_ifindex;

LOG_INFO("%s at index %d", str, ifr.ifr_ifindex);

if (bind(fd, (struct sockaddr*) &addr, sizeof(addr)) < 0) {

LOG_ERROR("Could not bind, error: %s", strerror(errno));

exit(1);

}

}

/*

* send_can_msg - sends a can message

* @frame - frame to send

*/

int CAN::send_can_msg(const struct can_frame &frame)

{

return write(fd, &frame, sizeof(struct can_frame));

}

/*

* recv_can_msg - recieves a can message

*/

int CAN::recv_can_msg()

{

memset(&recv_can_buff, 0, sizeof(struct can_frame));

return read(fd, &recv_can_buff, sizeof(struct can_frame));

}

/*

* release - kills the can device

*/

void CAN::release()

{

close(fd);

}

Getter function for reading the buffer in are defined in the header.

USB2.0/USB3.0/SATA Protocols:

While I have used/coded all these protocols, they require a lot more indepth explanation. I may explain them in better detail in a different post.

Wireless:

Wireless communications is an ever expanding field, with quite a lot of different protocol and modulation methods. This section will definitely get expanded as I have more time.

Bluetooth Protocols:

Bluetooth is a wireless protocol that works in the 2.4 GHz band, with only a 30 meter radius. There are several forms of Bluetooth, such as LTE. However the purpose of this post will only be to discuss the higher level protocols built on top of bluetooth, specifically L2CAP and RFCOMM.

NOTE: There are quite a few more protocols, the reader is encouraged to read more about them

L2CAP:

This is the bluetooth equivalent to UDP, which will be explained later on in Internet Protocols. This protocol uses datagrams, making it possible not to use a stream in order to communicate between devices. This allows for fast transmission and receiving. It is important to note that while this is close to UDP, it still allows for infinite retransmissions of lost packets. Here is the server code for a sample L2CAP program, the original code came from here.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <bluetooth/bluetooth.h>

#include <bluetooth/l2cap.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

struct sockaddr_l2 loc_addr = { 0 }, rem_addr = { 0 };

char buf[1024] = { 0 };

int s, client, bytes_read;

socklen_t opt = sizeof(rem_addr);

// allocate socket

s = socket(AF_BLUETOOTH, SOCK_SEQPACKET, BTPROTO_L2CAP);

// bind socket to port 0x1001 of the first available

// bluetooth adapter

loc_addr.l2_family = AF_BLUETOOTH;

loc_addr.l2_bdaddr = *BDADDR_ANY;

loc_addr.l2_psm = htobs(0x1001);

bind(s, (struct sockaddr *)&loc_addr, sizeof(loc_addr));

// put socket into listening mode

listen(s, 1);

// accept one connection

client = accept(s, (struct sockaddr *)&rem_addr, &opt);

ba2str( &rem_addr.l2_bdaddr, buf );

fprintf(stderr, "accepted connection from %s\n", buf);

memset(buf, 0, sizeof(buf));

// read data from the client

bytes_read = read(client, buf, sizeof(buf));

if( bytes_read > 0 ) {

printf("received [%s]\n", buf);

}

// close connection

close(client);

close(s);

}And here is client code:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <bluetooth/bluetooth.h>

#include <bluetooth/l2cap.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

struct sockaddr_l2 addr = { 0 };

int s, status;

char *message = "hello!";

char dest[18] = "01:23:45:67:89:AB";

if(argc < 2)

{

fprintf(stderr, "usage: %s <bt_addr>\n", argv[0]);

exit(2);

}

strncpy(dest, argv[1], 18);

// allocate a socket

s = socket(AF_BLUETOOTH, SOCK_SEQPACKET, BTPROTO_L2CAP);

// set the connection parameters (who to connect to)

addr.l2_family = AF_BLUETOOTH;

addr.l2_psm = htobs(0x1001);

str2ba( dest, &addr.l2_bdaddr );

// connect to server

status = connect(s, (struct sockaddr *)&addr, sizeof(addr));

// send a message

if( status == 0 ) {

status = write(s, "hello!", 6);

}

if( status < 0 ) perror("uh oh");

close(s);

}RFCOMM:

This is equivalent to TCP in terms of Internet. However this can act as a stream or datagram, which TCP can only act as a stream based socket. Below is sample server code taken from here.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <bluetooth/bluetooth.h>

#include <bluetooth/rfcomm.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

struct sockaddr_rc loc_addr = { 0 }, rem_addr = { 0 };

char buf[1024] = { 0 };

int s, client, bytes_read;

socklen_t opt = sizeof(rem_addr);

// allocate socket

s = socket(AF_BLUETOOTH, SOCK_STREAM, BTPROTO_RFCOMM);

// bind socket to port 1 of the first available

// local bluetooth adapter

loc_addr.rc_family = AF_BLUETOOTH;

loc_addr.rc_bdaddr = *BDADDR_ANY;

loc_addr.rc_channel = (uint8_t) 1;

bind(s, (struct sockaddr *)&loc_addr, sizeof(loc_addr));

// put socket into listening mode

listen(s, 1);

// accept one connection

client = accept(s, (struct sockaddr *)&rem_addr, &opt);

ba2str( &rem_addr.rc_bdaddr, buf );

fprintf(stderr, "accepted connection from %s\n", buf);

memset(buf, 0, sizeof(buf));

// read data from the client

bytes_read = read(client, buf, sizeof(buf));

if( bytes_read > 0 ) {

printf("received [%s]\n", buf);

}

// close connection

close(client);

close(s);

return 0;

}Here is the client code:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <bluetooth/bluetooth.h>

#include <bluetooth/rfcomm.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

struct sockaddr_rc addr = { 0 };

int s, status;

char dest[18] = "01:23:45:67:89:AB";

// allocate a socket

s = socket(AF_BLUETOOTH, SOCK_STREAM, BTPROTO_RFCOMM);

// set the connection parameters (who to connect to)

addr.rc_family = AF_BLUETOOTH;

addr.rc_channel = (uint8_t) 1;

str2ba( dest, &addr.rc_bdaddr );

// connect to server

status = connect(s, (struct sockaddr *)&addr, sizeof(addr));

// send a message

if( status == 0 ) {

status = write(s, "hello!", 6);

}

if( status < 0 ) perror("uh oh");

close(s);

return 0;

}Internet Protocols:

There are several protocols for internet, the most predominant ones include UDP and TCP. Named Data Networking is an interesting one, however still incredibly far to go before it can be fundamentally used by the general public. IPFS is another protocol currently being developed for a decentralized internet, unfortunately still very far to go.

UDP:

A very simple protocol where it is designed to be fast, but not necessarily reliable. There is no retransmissions for missed packets and there is no checks for dropped packets. The upside is it is incredibly easy to code up.

TCP:

This is a fairly complex protocol which was designed to be reliable, as a result it has a lot of slowdowns. These are handled with congestion control techniques. They however still do not fix all possible slowdowns.

Modulation for Wireless:

I will add more here when I have more time to work on this.

Most Important Tidbits:

- Make a text based communication protocol first

- Huffman encoding is a very good choice to lower the complexity of your commands

- CAN also has a wireless networking interface

- There are plenty of libraries which build protocols on top of CAN

- PLCs have an interesting way of handling wireless communications